|

|

||||

|

|

||||

|

|

||||

|

|

STRAIGHT AFTER THE CIVIL WAR The population of the village had drastically reduced mainly due

to casualties sustained in the bitter fighting during the wars. Even

though the morale in the village was somewhat subdued as many were

in mourning after having lost loved ones, the village still proceeded

with the three days of Easter celebrations. From Good Friday to Easter

Sunday the village square was alive to the sounds of drums beating

and ora (traditional dancing in a circle). It was mainly the younger

ones who danced whilst the women would gather around the outskirts

of the dancing and watch on. Two members of the Neretski band at the time were Mitre Genchev on

clarinet and Risto Novachkov (nicknamed Baikolo) on drums. Risto's

drum had a really strong skin that could take quite a pounding. Mikhaeli

Genchev was only recently married at the time and was part of the

group of boys I played and hung around with. Not once did Mikhaeli

and I ever fight or argue growing up. Mikhaeli was a very friendly,

lovable, and compassionate person. As he was recently married, he

wanted to lead an oro. He asked his father Mitre if he could lead

an oro. His father said "After this one". The day went by,

and it was always 'after this one'. The same thing happened on the

second day of celebrations. Early on the third day Mikhaeli said "Dad,

play me an oro and if it's about money, I will pay you." His

father kept saying I will play for you soon. Mikhaeli rounded up all of our friends and we went to my store to

have some drinks. Mikhaeli decided that he had had enough of his father

constantly ignoring his plea to lead an oro, so he was going to take

matters into his own hands. Mikhaeli had decided that if he wasn't

going to be given an oro then no one else was. He had decided to break

the musicians' instruments. After a few drinks to help him muster up the courage and with the

rest of the boys as support should things get out of hand and fighting

erupt, we walked down to stret selo. Mikhaeli once again asked his father "Will you play an oro for

me?" His father came up with the same reply - "After this

one". Mikhaeli then snatched his father's clarinet out of his

mouth whilst he was playing and flung it some distance, striking rocks

but surprisingly not breaking. From there he tried to pierce the skin

on the drum by giving it several swift kicks but was unsuccessful.

Mikhaeli then grabbed the drum with both hands and then kneed it until

the skin was pierced. Risto, the drummer, was enraged that his expensive skin was ruined.

We said to him not to worry as we would cover the cost of the damage

caused. Unfortunately, whilst Mikhaeli was breaking the musicians' equipment,

we didn't take note that the person leading the oro was a karafilok

(policeman). The policeman was Risto Dula, Fania Trenoa's husband.

If we had known, we would have waited for the next oro. By destroying

the instruments whilst the policeman was leading, it appeared that

it was done as some form of protest against the local constabulary.

Hearing the commotion, the astinomo (head of police in Neret) came

and gave Mikhaeli a massive slap to the face. Having witnessed Mikhaeli

receiving a slap to the face, his Teta Stoyanka, who was a large,

strong, solid woman grabbed the astinomo, spun him around several

times and sent him sprawling to the ground with his feet up in the

air. All of the villagers gathered around him, laughing at what had

happened. Mikhaeli's aunty said "I'll show you, you filthy dog,

who's nephew you are belting. I'll show you a beating." The police took Mikhaeli away and locked him up. To make sure that

he didn't receive a beating in jail one of his friends decided to

go in jail with him to act as a witness should Mikhaeli be unfairly

treated. Somehow word about the incident got to Mitre Bakalis (Pop (priest)

Tome's son) who was head of police in Rosen. Mitre is a relative of

the Genchev family. I think Pop Tome's wife and Mikhaeli's baba were

sisters. Mitre arrived in Neret a few hours later in his jeep and

organised soon after for Mikhaeli's release. Mikhaeli was lucky to

have got away with things as lightly as he did. Mikhaeli would come regularly to my store to catch up with me and

our friends. Unfortunately he didn't have money to shout his friends

and that made him uneasy. He would often say that it was embarrassing

receiving drinks from everyone and not being able to reciprocate the

gesture. We kept saying to him not to worry and that there will come

a time when he will have money and that he will be able to buy us

drinks. Sadly, it wasn't long after the Easter incident that he lost his

life trying to earn some money disarming a land mine. After the Civil War had finished in 1949, quite a few people were

killed or maimed from uncleared land mines. Many farmers accidentally

detonated these land mines whilst ploughing fields. Mikhaeli, my neighbour and closest friend, was removing detonators

and dismantling land mines so he could make money by selling the metal

(copper). He was very young, only about 19 years of age, and recently

married. He wanted to be able to buy his wife something special because

some of the other newly wedded men in the village had given their

wives something, but he hadn't. We were always telling him off, and

for him not to go and handle these land mines because they were far

too dangerous to play around with. Unfortunately, because he was so

poor, he felt that this was the only way he could make some money.

Mikhaeli's father had sheep and was reasonably well off but, in those

days, the older people were a bit unreasonable and unwilling to part

with what they had in order to help the struggling, younger members

of the family. Unfortunately, when Mikhaeli was trying to dismantle one of these

mines, it accidentally went off in his hands. I heard the explosion

and had an uneasy feeling that he was involved because it was only

the night before that I had been talking to him and telling him not

to risk dismantling these mines. I had a little store that I was running

at the time and when I heard the bang, I dropped everything, and I

raced up to where he was. I found him lying on the ground. He wasn't

crying nor yelling out. I started talking to him. "Mikhaeli,

what have you done?" He said "I have no arms, no legs. I've

seen, I have neither arms nor legs." He had dragged himself quite some distance down the mountain slope

from where the initial blast had occurred without limbs. I, to this

day, can't comprehend how he did it. I tried to reassure him by saying

"You have arms and you have legs," even though I could see

that he didn't and was in a very bad way. The blast was so devastating

that it had blown his hands off and I could see veins protruding from

his body as if they were spaghetti and some of his insides were hanging

outside his body - it is something that no man should endure and no

man should have to witness. I took off my jacket, pushed his insides back in and wrapped up his

body. I also took off my belt and strapped him together as best as

I could. His parents arrived soon after and they were screaming and

yelling. The shock was so great that his mother fainted. With the

help of some of the other villagers, Mikhaeli was taken to Lerin to

seek medical assistance. He was a very strong man and considering

the injuries he received from the blast, he still survived for another

24 hours. Unfortunately, the heavy blood loss was too great, and he

couldn't be saved. I will digress for a moment whilst talking about Mikhaeli Genchev. After my sister Fania died in 2010, my son George and his wife Anne

convinced me to go back with them to see my sister Ristana and my

brother-in-law Risto before I would become too frail to travel. Over

60 years after Mikhaeli's death, I returned to my village in 2011

after not having been back from the time I left in 1955. Straight

after arriving in Neret and meeting my sister Ristana and brother-in-law

Risto and placing our luggage in the rooms where we were staying,

we were all excited to walk through the village and in my case to

see what changes had happened over the time that I had been away.

The real astonishing thing is that the very first person that we came

across as we were walking through the village was a lady called Lefa.

We started talking and Lefa asked who we were and whether we were

from this village. After I told her I was born in Neret, and she roughly

worked out my age, she asked if I knew her brother, Mikhaeli Genchev,

who was quite a few years older than herself. I said that I knew him

very well and that he was my best friend. Lefa told me that on the

day that he had been killed she was being looked after by relatives

in a neighbouring village and being quite young, was never really

told exactly what had happened. I told Lefa I can tell you exactly

what had happened. As I started telling her what had happened, we

all broke down in tears. Instead of talking in the street, Lefa asked

if she could meet with me so we could talk some more about the past.

We ended up meeting and chatting a few more times before my short,

three-week stay was over. I was told Mikhaeli's wife remarried. Mikhaeli's wife was a lovely woman from the Vlaoi (Vlahos) family. She married a man from Kalinik. Whenever they visited Neret to see friends and relatives they would always light a candle for Mikhaeli.

I enjoyed catching up with my sister Ristana and her family and a

few of the people I had known from my younger days in the village

who were still alive. The village had changed greatly in that time

with now only about 300 residents remaining. Many of the nivie (fields

that were used for agriculture) were now overrun by thick scrub. Most

of the younger people had moved to the larger towns in search of work

and only the more senior residents of the village appeared to have

an interest tending to their plots of land. When I left to go back

home to Perth, my sister and I embraced each other for the last time

and she said "This is probably the last time that we will ever

see each other in person." She was right - sadly nine years later

in 2020 she died from complications caused by a broken hip. After the Civil War I went back to the village and ran a small store

for a few years and applied my skills learned in Lerin. Ideally, I

would like to have kept living in Lerin and to open a store there,

but it was felt it would be best for all of us to go back to Neret

and try and get some semblance of family unity again. Towards the end of 1953, I did 18 months of national service. Initially,

I was based just outside Solun in an area called Corintho. When I

arrived there, they were looking for people that may have had some

sort of experience other than just that of being a farmer. They needed

someone who could do the ordering and shopping to feed the troops

and was able to do basic office duties. I had a bit of experience

because I ran my little business in the village and from my time in

Lerin selling goods. My grasp of the Greek language was also quite

good considering I only had two years of primary schooling. Having

to converse with Greek teachers and policemen who would frequent my

store improved my vocabulary immensely. We were lined up and each one of us was asked what previous work

experience we had. One after the other the answer was shepherd or

farmer. When they got to me, I said that I was a shopkeeper. They

said "Where have you been hiding? Put down your gun and come

with us." From Monday to Friday, I was doing shopping for the

army in Solun. A few months later, from there, I was transferred to

Nesrum, a town not far from Kostur. After a few days being there,

the officers called me into their office and said they had heard that

I was educated and that they would like me to work in the army post

office. I didn't let on that I had minimal schooling but simply went

along with their requests. I enjoyed my time working in the post office. I was lucky in that I only had to do 18 months national service because

the government couldn't afford to keep soldiers too long because it

didn't have the finances. Previously, soldiers had to serve for three

to four years. Some photos of my time doing national service from 1953 to early 1955.

The Life Story of Tanas Kirev

|

My

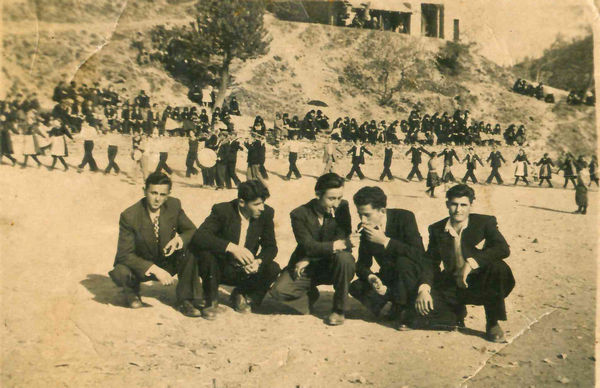

four best friends I grew up with in Neret. The photo was taken in

Stretselo (village square. From left to right: Me, Mikhaeli Genchev,

Vasil Markov, Vangel Markov and Tanas Andriov. Circa 1947.

My

four best friends I grew up with in Neret. The photo was taken in

Stretselo (village square. From left to right: Me, Mikhaeli Genchev,

Vasil Markov, Vangel Markov and Tanas Andriov. Circa 1947.