|

|

||||

|

|

||||

|

|

||||

|

|

And Another Thing There is another thing I can say about teaching, and additionally

this is not the last thing as far as the education system of Victoria

if not all of Australia is concerned. It is just a small part, one

part of many things that I observed during my time with the Education

Department. The vision of a man painting the main office of the Defence Standards

Laboratories (DSL) back in 1972 where I worked still intrigues me.

He had a degree in civil engineering and he was painting walls for

a living. And that is because he liked painting, as someone pointed

out to me. Strangely enough I like painting and I like doing many other things

as well, like engineering and explaining technical stuff. There was

no career path in civil engineering via painting walls for that civil

engineer at DSL. Similarly, I wasn't seeking a career in either teaching

or in engineering through my involvement with schools, teachers and

students. I was simply reacting to the environment that I found myself

in, I was being an existentialist. There were unforeseen benefits for me in not striving to advance

my position up to the principal class. I wasn't enticed by the lure

of extra remuneration that career advancement provides and I didn't

have an egotistical need to advance my second-choice career beyond

the classroom teacher. I was happy with teaching physics and maths.

This was a huge academic and financial advancement for me. It was

a quantum leap from herding sheep in Macedonia. So now I could sit

back, observe and enjoy the social interactions that went on at schools

and I could participate in interesting extracurricular activities

of my choice. By now Antonio and I were very close friends, our friendship extended

beyond school hours. And Nick, the student teacher, mastered the skill

of teaching, which freed me of my obligations to him. Now an opportunity

presented itself for me to make a beneficial change to my lifestyle

within the schools and I was in the position to take advantage of

it. It all started when Northcote Tech announced that it had a teacher

"in excess". I chose to declare myself in excess at Northcote

Tech and I asked the principal to relocate me to Mitcham Technical

School, which was no more than one kilometre away from my home. The

benefits of this relocation were: 1. Closer to home, saving on transport costs and reducing travel time. 2. I would cycle to work for exercise and I could cycle home at lunchtime to see my baby daughter. 3. An opportunity to make new friends. 4. Mitcham Technical School had a good reputation and it was a fully

functioning technical school with a well-equipped workshop, which

made it an ideal school for technological projects. The transition between the two schools was arranged and it went

smoothly, but my reception at Mitcham Tech wasn't smooth and it was

different to that at Northcote Tech. In fact, it was so different

that it didn't leave a positive-memorable impression on me. I had

a cold reception at Mitcham Tech, especially in the staff room where

nobody looked up as I was introduced to the staff. I never entered

that staff room again. I kept warm, figuratively speaking, by the reunion at Mitcham Tech

with my friend Aleko Papas, whom I met at our training school of Ringwood

Tech and who is now another of those lifelong friends. In due time, Aleko and I met a few other teachers who felt the cold

ambience at Mitcham Tech and within a semester at the school we formed

a group of teachers to stay warm with and to drink Turkish-style coffee

as we socialised during morning recess. The group consisted of Aleko Papas - Greek; Johannes Dajik - Dutch;

Lee Ching - Malaysian; Xin Hong - Chinese; Ian (Major) Savic - Croatian;

and George Harrison - he wasn't of an Anglo-Saxon background despite

his name, he was Palestinian, but he insisted that he was a French

Canadian. And of course there was me, the Macedonian who brewed the

Turkish-style coffee every morning recess. There were few other teachers of other ethnicities who kept to themselves,

notably a physical education teacher from Macedonia who represented

his country at the Olympics, another physical education teacher who

played soccer for the Dutch national team, and there was Orlando Aprila

who persevered towards an impossible goal of becoming a school principal.

I say impossible because he didn't read the body language of the

school administrators who were brought up during the reign of the

White Australia policy, even though the White Australia policy was

abolished by the time Orlando was striving towards his goal. The school

and Education Department administrators could not adapt quickly enough

to the workplace changes that were taking place during the late 70s

and 80s. It takes generations to affect changes involving racial matters.

Up to the age of his retirement, Orlando did not progress past level

6 (an automatic incremental promotion) classroom teacher. That is

even though he had a university degree in chemistry and a diploma

of education and he was bilingual. Having an Italian background impeded

his career progress at Mitcham Tech. Sadly, Orlando also missed out on drinking Turkish-style coffee

with us and de-stressing during the Turkish coffee breaks because

he sided with the ambitious group of teachers at Mitcham Tech. Destressing

is what saved many of us from depression during the "high school

and tech school" amalgamations and during the protracted and

eventual closure of the technical schools. Members of the Turkish coffee club still see each other and discuss

such issues, long after our retirement from teaching. The Turkish-style

coffee club was therapeutic for us, the ethnics. Several years went by, the Turkish coffee club survived, and it

was still a mystery to the rest of the staff. Meanwhile, the car park exhibited some interesting cars (mainly

mine), which attracted the attention of an inquisitive trade teacher

who happened to like interesting cars, and who was appropriately named

Neil Wolseley (but not a descendent of the founder of the Wolseley

motor car company). That year the trade department decided to enter into a newly introduced

car fuel-economy competition (dubbed the Shell Mileage Marathon) that

was sponsored by the Shell motor oil company. The trade wing of the

school sent Mr Wolseley to ask me, the driver of the interesting cars,

if I could help with the design of a suitable car for the car fuel-economy

competition. The design and construction of an efficient, minimalist three-wheeled

car was what I was waiting for. Needless to say, the car was completed

in time for a run at Amaroo motor racing circuit in NSW. I calculated

the required engine power and the gear ratios of the car that would

be sufficient for it to perform to the specifications that were stipulated

by the organisers of the event. But I wanted to test the vehicle to make sure that it would be able

to successfully complete the economy run. According to my calculations,

the car with a 30 kg driver in it had to attain a speed of at least

15 kph within a distance of 20 metres from a standing start to successfully

complete the stipulated course in the specified time. The only level surface of more than 20 metres in length that I could

find was within the school buildings. The long corridor of the maths

wing was an ideal test track for our entry into the Shell Mileage

Marathon competition. The 30 cc two-stroke engine burst into life,

the 30 kg driver opened the throttle of the engine and the car roared

along the corridor at twice the required speed. The head of the maths

department grumbled under his bushy beard that we disturbed his maths

class. But he couldn't hide his green-with-envy facial expression.

Everyone else was conspicuously silent or absent. Somehow the secret got out and it found its way into the pages of

the Herald-Sun newspaper. Next day a Shell oil company representative

came to our school to congratulate the team. A few days later I received a call from America via a physics teacher

whom I knew and who taught at Camberwell Grammar during the teacher

recruitment period. He informed me that our car project made it into

the American evening news. The segment stated: Mitcham High School

tested their racing car in the school's corridors (they made two errors,

the class of school and the type of car). Within a week a TV crew came to our school to film and to produce

a short episode of this new extra-curricular activity that was taking

place at a technical school. The episode was shown on a television

science program titled "What's Out There?". The participating

students who were featured in the TV segment spoke enthusiastically

about the project, without prior rehearsals. This was how I wanted the project to evolve. This was a project

of major educational benefit - five teachers and twenty students were

involved, all with the blessing of the school council that funded

the project. The school council also paid for the hire of a medium-sized

bus and for the training of one of the staff members for his bus driver's

licence. The bus driver got his licence, but he wasn't taught how to drive

a diesel-powered bus. "Change into a higher gear now, don't rev the engine,"

I advised him. "Huh, you think you know how to drive a bus now," an ignorant

teacher remarked. "He is right, diesel engines don't need to be revved,"

replied Mr Wolseley. This was a technologically important event and a serious undertaking by a school that was participating alongside formidable opponents such as the Ford Motor Company, several colleges of advanced education, some universities and many private enthusiasts, one of whom towed his amazing looking car all the way from WA. I was happy that we made it to the starting grid.

On the day of the run I walked with my two drivers around the racing

track and showed them the path that they should follow during the

run. The first corner might have needed braking, I thought to myself,

but I instructed the drivers not to use the brake as this eats into

the fuel consumption of the car. "Approach the corner slowly, use the whole width of the track

and accelerate slowly after the corner," I said to them. To stress

the point even further of not using the brake, I taped a sheet of

A4 paper over the brake pedal and said to my number one driver: "I

don't want to see a footprint on the sheet of paper." The economy run was executed perfectly by young Peter Allis; he

completed the run with twenty seconds to spare and recorded an amazing

401 MPG figure for fuel consumption. Mathew, the second driver, who

was transported to the venue independently by his father, was given

an unofficial run and completed it within the allocated time and probably

recorded a better fuel consumption than what our number one driver

did. Mathew was thrilled with that. We could not have done any better.

We returned back to school triumphant with a Best Inaugural Team

trophy and $250.00 in prize money. The first teacher to congratulate

me on running the event was the one who questioned my know-how about

the diesel bus. The reception back at school was as cold as the South Pole. The

administrators and the humanities department ignored us. They thought

that we went on a personal adventure (they were partly right, at least

as far as I was concerned); one staff member asked if we enjoyed our

personal trip to NSW. The trade teachers on the other hand couldn't hide their disappointment

that the science department hijacked a trade department project and

completed it successfully. Nobody spoke to us about the event, but

they immediately started designing the next year's entry. As soon as we came back from the Amaroo racing track, I heard that

a group of electric car enthusiasts had formed the Electric Vehicle

Association of Victoria and organised a race for home-made battery-powered

cars to be held at the VFL Park in June 1986. The Shell Mileage Marathon

car was ideal for this competition. All we had to do was to fit a

12 kg lead-acid battery into our car and to exchange the petrol engine

with an electric motor. By June 1986 the electric battery powered car was on the starting

grid, ready for a two hour Formula 1 style race on a track mapped

out on the VFL's car park in Glen Waverley.

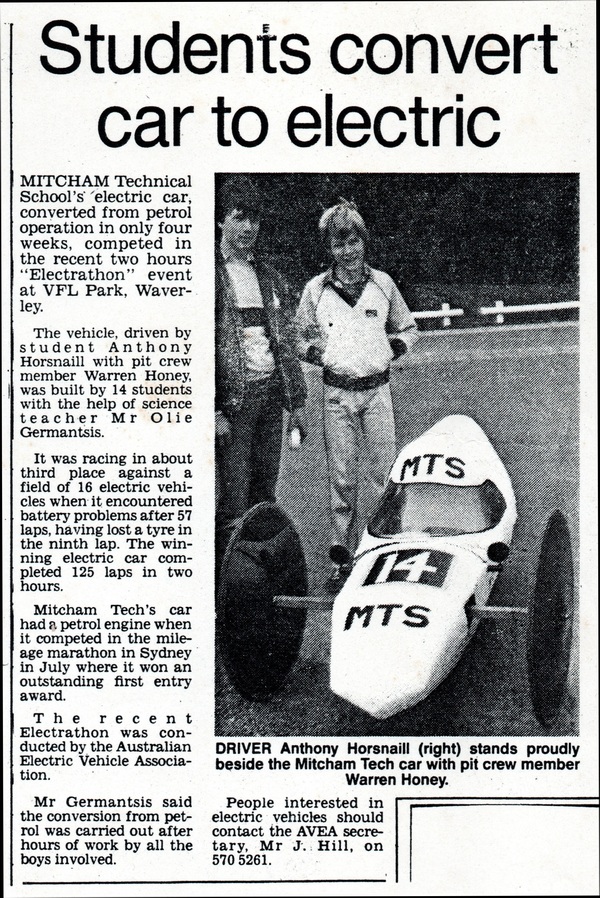

A local newspaper article about the students' entry in the Electrathon

electric car race. Mitcham Tech's car started well and was leading the competition

for the first hour until it started to slow down at a concerning rate

and it eventually came to a halt. The battery ran out of Coulombs

(electrical charge). Unbeknown to me, new batteries need to go through a charging and

discharging cycle to get the maximum energy out of them. Our small

team gained valuable experience about electrically powered cars. Back at school, the battery-powered car project was ignored again

by the academics and was shunned by the tradies who vowed to build

their own Shell Mileage Marathon car. The administrators on the other

hand were preoccupied with the impending amalgamation of the tech

school with its sister high school and had no time for our battery-powered

car. After the unappreciated work that I put into the car projects, I

distanced myself from the extracurricular activity and concentrated

on inner school activities which included introducing cycling as a

sports option for the students. I love coincidences and this coincidence involving cycling, a car

and a hatchet is extra special as it showcased my apparent ability

of diffusing dangerously violent situations. Whilst I was riding with the cycling sports group on the streets

around the surrounding suburbs of Mitcham, I saw an abandoned car

in the backyard of a house in Blackburn. It was a convertible Triumph

Herald in original condition (these cars are collectable now). After

school, on my way home I purchased the car at a bargain price of $50.00

and drove it home to include it in my car collection. But I lost interest in the car and I offered it to one of my cycling

students, Michael Schuman, at the same bargain price of $50.00. Michael

and I rode two-abreast during the sports activity and spoke enthusiastically

about his future plans regarding the Triumph Herald. Those discussions

formed a trusting relationship between us. That trusting relationship

was put to the test one day in the school yard. I was on yard duty when a riot started at the far end of the school

yard. Students were chanting and two teachers were rushing to the

scene where a student was wielding a hatchet and was cutting down

small potted trees. The two teachers were directing the students away

from the violent scene. The teachers appeared startled and warned

everyone to stay away. I saw that the culprit was Michael, who was menacingly wielding

the hatchet. I walked up to him and calmly asked him to give me the

weapon. "Give me the axe, Michael," I said. Michael handed me the hatchet as if he was giving me a piece of

his birthday cake. The tense situation calmed down and there was an

air of disbelief as Michael and I walked two-abreast towards the vice

principal's office. The other two teachers were stunned by the way

I diffused the situation and how I calmed a distressed student. That day Michael couldn't hold his rage after he found out that

his parents had divorced. Academic and sporting activities at Mitcham Tech settled down to

normal again. And then I was summoned to the vice principal's office

for what I thought might be a delayed congratulatory appraisal for

either the Shell Mileage Marathon car project, the electric car project,

the cycling sports activity, or the disarming of the armed student.

But no, I was invited to the vice principal's office for a mysterious

interrogation. The vice principal positioned herself on a high chair

and offered a low stool at her feet for me to seat on. This is a standard

intermediating method used to intimidate students. Mrs Blueberry looked like a character from a Charles Dickens novel

who was reading a book by the fireside, the only things missing were

a cat on her lap and a blanket covering her legs. She began interrogating

me in a deceivingly casual way. She had taken the customary approach

of interrogation that was used in shaming petty criminals in Charles

Dickens's era. Mrs Blueberry began with the usual customary complementary

statements. 1. "You know that as a professional teacher, you have responsibilities." 2. "The school has set-working hours." 3. "You are well paid and you are required to reflect this by

your actions." Back at the Turkish coffee destressing hub I related my confrontation

with Mrs Blueberry to Aleko, who immediately cleared the bizarre mystery.

He told me that the previous day he was seen leaving the school early

and that I must have been mistaken for him. Aleko and I are not twins,

there is a substantial physical difference between us. But I understand

the mistaken identity, the informant would have told Mrs Blueberry

that "one of the Greeks absconded". There are so many more examples that I can tell you that are based

on prejudice, but I will describe the most blatant examples of pre-judgements

that I observed and then I will close this chapter. At the beginning of 1987, I volunteered to go to Burwood Technical

School. It was the last stand-alone tech school and there I met a

scruffy looking trade teacher who was full of anger and was not afraid

to express it. His name was Robert Butcher. He was a carpenter by

trade, but he taught a maths-based subject that hardly anybody understood

including the maths teachers. He taught 'solid geometry'. I saw something

of myself in him. We both came from a poor background. He told me

that he used to hunt rabbits for food around Hobson Bay when Hobson

Bay was open farmland. He showed me how to cook rabbit terrine. From

then on I socialised with Butch, as he liked to be referred to. And then one day Mrs Bloomfield, a teacher from the humanities department

who lives in Surrey Hills and whose daughter is a dancer in the Melbourne

Ballet Company, approached me. Mrs Bloomfield, who was at the top-end

of the social scale, asked me: "How can you socialise with that

feral person?" I gave her a true assessment of Robert. I told her that: "Mr

Butcher might look a bit rough around the edges, but he has a heart

of gold. I have seen how he treats his wife and his two daughters,"

I explained to Mrs Bloomfield. Well now, you have to imagine the "Toyota ad" where a

person jumps, clicks his feet together and says "Oh What A Feeling"

to visualise the next scene. Picture Mrs Bloomfield skipping away

with delight and I could just faintly hear her telling a colleague

of hers: "Olie said that Robert Butcher has a heart of gold."

Are people like Mrs Bloomfield for real? Yes, they are real and

that's why we have prejudice, and that's because one person judges

another person relative to his frame of social reference. I bet Einstein

could have formed a "prejudice" equation for this human

trait. Butch on the other hand returned my compliment when the head of

the science department of Burwood Tech, who thought that he was as

smart as Einstein, because he drank his coffee from a beaker, asked

Butch "Why do you hang around with that wog?" Butch answered thus: "Because I like him and that he is smart."

I was horrified at observing acts of prejudice at Burwood Tech for

the next three years before it closed down without amalgamating with

a neighbouring high school. By now the tech school students were out

of control, their educational future was uncertain, and corporal punishment

was replaced with a form of collaborative agreement between teachers

and students that students couldn't understand and therefore the discipline

method did not work. Evidence of students being out of control was not hard to see. A

one-eyed person could see it. I saw one act when Mrs Bloomfield was

skipping with joy along the corridor. I managed to get a glimpse of

a teacher's hair on fire in an adjacent science room. Felicity, the

teacher from Northcote Tech, was now transferred to Burwood Tech to

have her hair charred by an out-of-control student. Teachers had no effective method of controlling students and they

didn't have the support of parents. One mother by the name of Mrs

Murphy came to me for a parent-teacher interview regarding her son,

named Taylor, to bluntly tell me that I could not control the class

that her diligent son was in. "Taylor says that you can't control your classes, Mr Gee errr

mant sus." "Yes, you are absolutely right, Mrs Murphy. But it is Taylor

who is the most disobedient student in my class. Could you please

help me, Mrs Murphy, and tell me how you control Taylor at home?" Mrs Murphy stood and left before I finished my question. Oh, how I wished I was back at Northcote Tech where parents of ethnic

backgrounds would come and ask "Is Johnny good?" "Yes, Johnny is very good." "If Johnny is no good, you smack at school, I smack at home.

No more problems with Johnny." The technical school era that started in 1873 came to a regretful

end in 1992. A new and undefined educational era was now emerging.

And then I was "exiled" (exiled is not quite the right word,

next chapter will deal with this) to a genuine secondary college which

made my parents proud of me. Because now they could tell their peers

that their son is a "college professor". Before I went to Brentwood Secondary College, and where I encountered a different form of prejudice, which will be described shortly, I wrote a poem to mark the end of the technical school era. And then I asked "Einstein" to read it out to the school staff because of his clearer Aussie accent. THE OLD TECH Where are your sons? An Aussie In A Parallel Universe

|