Zelnik, Zbog and the Gods

Remembering the Recipes that Bind Our Diets to Our Deities

By Chris Christou

Printable

Version

Printable

Version

In the Old Country, in times that we can no longer sense, there stood

God among the people. For as long as they could remember, the people

had been of that soil, they could remember working it and being worked

by it. While the churches had persisted in the villages since time immemorial,

their prayers' sonic supplications were set over their fields and that

is where they found Him.

The Macedonian word for God is bog, and in the old days the

word for wheat was zbog. Wheat was the accent on the name of

God, the sound that preceded divinity and cradled it among them. Wheat

was their God, the field, their ministry, and the barn their temple.

Throughout the world, there are stories about the enduring and regenerative

matrimony between family and food, between home and harvest, between

the dead and the digested, about how such people, wedded to place, understand

their deities and their diets to be one and the same. This is one of

those stories.

The Flight and The Food

As a child, my sister and I had the great good fortune of being raised,

in part, by our baba and dedo. It was the late 1980s and

our parents were off working themselves to the bone (mostly for us).

This meant that the Old Country tradition of the elders looking after

the youngsters survived the mass migration of the village from western

Macedonia to east Toronto.

My ancestors managed to withstand four centuries of Ottoman rule, but

the collapse of the empire conjured a firestorm in the Balkans whose

ghosts continue to haunt the region. In the first half of the 20th century,

their villages became revolving doors for the occupations of countless

neighbouring armies. The local men were conscripted. Everyone, children

included, was forced to speak a foreign tongue. One of my babas remembers

the policemen, pressed against the family's house at night, listening

in for any whisper of Macedonian, a crime whose punishment included

flogging, jail time or being tied to a post for days on end in the town

square. In the 1950s, as the ashes of war began to settle, the borders

between communist Yugoslavia and fascist Greece were set to be petrified

with barbed-wire fences, right down the middle of the lands my extended

kin inhabited. ‘Choose,' they were told. Not unsurprisingly, like so

many in the region, they left, rarely if ever speaking of these things

in our presence.

My baba and detho on their wedding day. Somewhere in Aegean Macedonia,

circa 1950.

We were blessed in that way, for a time. But not everything survives

exile, and usually it is the memory of migration that's the first to

go. In its place, we often find the gastronomy of a people, cultivating

and sometimes hospicing the remnants of culture. My family was no exception.

Arriving in Canada in the 1960s, many of the ex-villagers began working

in restaurants, a typical tour-de-force for recent immigrants. Fresh-off-the

boat often means right-into-the-kitchen, and, for those who can afford

it, into one that can maintain the village hearth and hospitality as

a means of survival. To thrive in a new, alien and often hostile world,

people utilise what they know, and for many that includes the indelible

and ancestral recipes they secretly stash away and smuggle through customs.

While my family never opened a Macedonian restaurant, the Old Country

aromas and flavours flowed through their kitchens. Their recipes were

resurrected in the New World, feeding the umbilical cord of memory that

connected there and here, then and now, us and them.

Our Spiral Sustenance

Among all of our baba's dishes, there was one that was sacred. Zelnik,

they called it. In the Old Country, our people only prepared it for

special occasions, which usually meant saints' days, baptisms, weddings

and funerals. As in many cultures, certain foods are reserved resolutely

for ceremony as the sustaining, ritual reminders of life's cyclic celebrations.

To put it another way, the appearance of specific foods, like the appearance

of certain dates, the changes in the weather and the shape of the village,

signify the perpetuation and vitality of ceremony. It is ushered in

through the kitchen as it is in the fields, as people sow and reap,

as they mix and mould the sustaining bounty of their soils. If there

is no field and no farming, what becomes of the ceremony?

If there is no ceremony, what becomes of the dish, of the diet, and

of the deities?

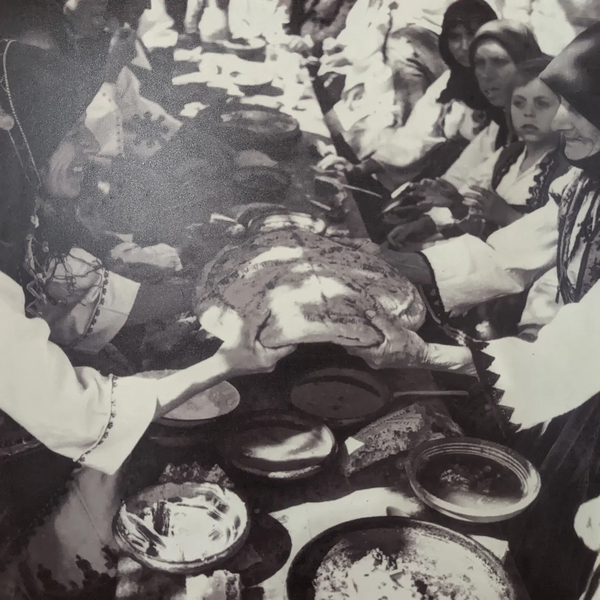

Macedonian

peasants preparing for a meal.

Macedonian

peasants preparing for a meal.

As a child in Toronto, zelnik quickly became my favourite food, and

our baba would make it as much as she could whenever we were around.

Removed from the place her people knew as the centre of the world for

as long as they could remember, we became the occasion for ceremony

in her days. She, like many of her sisters, aunts and babas, were the

guardians of hearth, hospitality and memory. They, the arches of the

familial and communal thresholds, ensured that their ceremonies would

persist in exile. From morning till afternoon, she spent hours spreading

out the skin thin layers of hand-formed phyllo dough, painting them

with butter and egg wash, and filling their innards with brined cheese

and sometimes spinach. She would then carefully fold the dough into

long serpentine rolls and coil each one around itself until it took

the shape of a spiral. These hand-woven, wheaten prayers were then left

to Grandfather Fire to bake, and if well-wrought such a petition would

provoke a golden sheen on the surface, signalling the birth of another

zelnik.

During our New Year's gatherings, the babas observed an ancient tradition

related to St. Basil. They would hide a coin in the zelnik, then carefully

cut the spiral into small sections, ensuring everyone had a piece. Whoever

received the auspicious slice would be blessed with good luck (and often

money) for the following year, a small manifestation of the family's

continued fortune.

St. Basil

For my people, as for many others, zelnik was a cornerstone of immigrant

identity, the breadcrumbs of memory laid down like pathways by the ancestors.

They are also often the last thing to disappear from that path after

the newcomers shorten their names, cast off their mother tongues, after

they trade in their traditional clothing for department store bargains,

their craft traditions for office jobs, their dances and rituals for

modern rites, and their myths for history.

However, when still stewarded, a people's foodways can root a sense

of identity. This is what zelnik did for me. It was ours. It

belonged to us and staked a claim as something that made us Macedonian.

It offered a quintessential connection to an ancestral homeland, to

culture, and to the dead. But as it turned out, zelnik is part of a

looping lineage that can pry us from the pitfalls of ethnicity and nationality,

of the overzealous identification with the ‘I' that often arrives with

the seductive satisfaction of knowing my heritage, my

history, and my culture. The majesty and mystery of food is that

it is never for you and never has been.

The Subversion of a Singular Identity

After our baba's death, I slowly forgot about her cooking, tasting

less and less of it as the years went by. Recently, however, alone in

my apartment, I was stopped dead in my tracks by the overwhelming aroma

of her freshly baked zelnik.

The ancient odour prompted a web search. Not unsurprisingly, what arose

was a litany of mouth-watering photos. One of them popped up with a

location attached. It was a restaurant in Turkey. ‘Wow, they have zelnik

in Turkey?' I thought. Then I found a cookbook online with a zelnik

recipe in it, but there was no section on Macedonia. The recipe was

in the Ukraine chapter. Later on, while hanging out with a Bulgarian

friend, I mentioned zelnik and described it to her. ‘Oh, that's burek,'

she responded. As it turns out, the Turks, the Greeks, the Romanians

and almost every other people in the Ottoman-influenced region have

their own name (and version) of zelnik. In some cultures, for example,

there is no spiral pattern baked into the bread.

The story's roots expand as they deepen. Before my family emigrated

to Canada, before incessant wars and cultural genocide came upon them

in the Old Country, Ottoman control spanned North Africa to the Persian

Gulf to the Balkans and everything in between. For half a millennium,

colonial trade and travel persisted under a system of relative religious

freedom (between Muslims, Christians and Jews) and this ensured a veritable

kneading of the cultural grain.

The roots of the word burek, zelnik's better-known sibling, come from

the Turkish borek, meaning ‘stew'1.

Like mole in Mexico and curry in South Asia, these names commonly

refer to a plurality of flavours, of many seeds and roots. While the

etymology of burek stretches back to ancient Persia, the origin of the

recipe itself is unclear. Some claim that it arrived from Central Asia

by way of Turkic nomads, some consider it a dish of the Ottoman high

court, while others see a link to Byzantine times.

Like its Aegean and Anatolian analogues, zelnik was a colonial dish,

one that became indigenous to each of those places over time. The people

honoured their manner of being in and of place by ensuring that their

own local, cultural and ceremonial ingredients were pressed into the

dough. Their maker's mark, in other words. Zelnik is as Macedonian as

burek is Bulgarian as placinta dobrogeana is Romanian, all of

which are inherited through colonisation. This is to say that sometimes

they don't belong to a single people. Burek is also the national dish

of the Macedonian state. By planting the dish in the local terroir,

each community plunged their roots into the assimilating ground of empire.

Each provides a path towards restoring ancestral memory, and subsequently

remembering how it is forgotten.

I'm reminded of the words of a friend and elder, the culture activist,

author and grief-worker Stephen Jenkinson: ‘The enemy of my ancestor

is also my ancestor'. The nuances in my people's traditional dress,

in their architecture and dance, even in my own appearance, are all

consequences of the conquest, fusion and confusion that arises. Just

like zelnik. The wars, the persecution, the migration, the ceremonies,

the celebration and the love. Every ingredient is added. All of it.

Cradled and cooked, it is nourishment and memory. All are eaten and

all are fed, and in this way we begin to undo that enmity, piece by

piece.

Two

Macedonian peasant families breaking bread.

Two

Macedonian peasant families breaking bread.

A Moveable Feast, A Migratory Famine

Years ago, I landed on the semi-desert shores of Oaxaca, Mexico. I

was lucky enough to begin an apprenticeship with culture, with what

it revealed and what it concealed. In the markets, at the molinos,

in the bowls and on the plates of the people, one can peer into the

bubbles in the bread and beverages to know something more of place and

time. My attention led me to an old understanding, one contained and

carried throughout many parts of the world.

In certain cultures of southern Mexico, cacao and maize are still remembered

as deities. Depending on where and when you are, the names, forms and

functions can be distinct, but they are almost always divine and personified

as such. While being worshipped as gods, cacao and maize are also known

as ancestors – the first ancestors – of human beings in Mesoamerica.

In the Popol Vuh, the Quiche Maya creation story, the first fathers

are both made of maize and subsequently fed it in order to become fully

human.

The Quiche are not alone. Countless cultures held and hold their principal

foods, their staple crops, and the animals they husband as ancestors.

One Hunahpu (maize) in the Mayan world, Dionysus (wine)

in Greece, Inari (rice) in Shinto Japan, Axomamma (potato)

for the Inca, Heryshaf (sheep) in Egypt, and Maxayuawi

(deer) for the Wixarika. Zbog (wheat) for the Macedonians.

Scene

from the Popol Vuh in which the Hero Twins reincarnate their uncle as

the Maize God.

Scene

from the Popol Vuh in which the Hero Twins reincarnate their uncle as

the Maize God.

When we honour ancestry, we feed the divine among us. When we understand

the animals and plants we eat as primordial ancestors, we can begin

to coax from the crumbs what it means to commune together, what it means

to be nourished by the dead and the divine, and what it means to be

descendants of each.

Zelnik is an example of how the enemy of my ancestors is also my ancestor,

how each of them, mostly by virtue of being born into their circumstances,

are folded into the sustenance that fed my family long enough so I could

be here today, writing this for you. Odds are that the stories are not

all that different among your people.

Traditional food and drink are not representations of lineage. They

are not symbols of ancestry. They are ancestry. In some cases,

the foods themselves are the bodies and blood of ancestors transformed,

moulded by descendant hands to remake and remember the ancient relationships

between the living and the dead who sustain them. In other cases, the

foods themselves are the guests of honour, the occasion for the ceremony,

the living memory of the sustenance that kept your people alive long

enough so you could be reading this today.

To understand what is hidden in our nourishment is to know what we've

allowed to go unfed, and whom. To deny the inherent diversity in ancestry

because it doesn't suit your politics or morals is to make a monocultural

Monsanto field of memory. It is to reproduce what made your people conquerors

or conquered in the first place. It is to consume instead of commune.

It is to only ever ask what you are eating and never whom.

Today, many of the fields surrounding the villages in western Macedonia,

like the fields surrounding my home in Oaxaca, are examples of such

amnesia. The Gods of Wheat, like the Gods of Maize, have become relics,

reconstituted as alimentary fuel pumps, nutrition sources and natural

resources, served by supermarkets, biotech companies and emigration.

Similarly, the people of Oaxaca are the inheritors of centuries of brutal

conquest, of cultural genocide and exile. The American dream – or nightmare

– tempts villagers into the cities, slowly emptying the countryside,

uprooting the food-borne relationships that blend together the living,

the dead and the divine into masa, the dough of community.

A

Mexican peasant farmer carrying his heriloom corn/ maize.

A

Mexican peasant farmer carrying his heriloom corn/ maize.

After a day's work in the jungle, I'm often invited into my compañeros'

homes, offered their ancestral hospitality, fortified and inspirited

by their grandmothers' criollo tortillas. I witness first-hand

the often dire dilemmas visiting their villages and all at once am transported

to my baba and dedo's, a century ago. I wonder if the spiral zelnik

and the lunar tortilla aren't both anointed tutors of time, holy reminders

of resilience and relationship, constantly at risk of slipping from

view.

In the few feasts and fields in which these ancestors are still kept

alive, nourishment arrives as memory – the collective memory that we

are fed and entered into. Communing with the millennia-old lineages

tying people to place and food, we are braided into that double-helixed

digestion with each bite. What it might offer us is medicine, food for

our times: that the lineage of sustenance continues to be forged not

because the people in question were your ancestors, not because of what

the food is, but who it is.

This is the recipe that my baba inherited, and that she has left to

us. These are the ingredients of zelnik, the divine harvest of a people.

When these things coalesce, ceremony can begin. When they are forgotten,

the world is famished.

This is the food.

This is the grace.

1. It is important

to remember that recipes, like words, have many versions, histories,

and lives. Here is another root of borek: "According to the Austrian

Turcologist, Andrea Tietze, ‘börek' comes from the Persian ‘bûrak',

which referred to any dish made with yufka. This, in turn, probably

came from the Turkic root, bur-, meaning ‘to twist' – an allusion

to the way thin sheets of dough had to be manipulated to produce a layered

effect." #

Originally Published in Dark Mountain Issue #23 - Dark Kitchen (2023).

You can purchase a copy and read the other written fermentations here.

Chris Christou is a culture activist, writer, and podcaster. See http://www.chrischristou.net

January 2024

Copyright

Source: www.pollitecon.com