Interview With Tanas Mechkarov

Macedonian Australian businessman Tanas Mechkarov was born in the

Macedonian village of Neret (Polipotamos) in northern Greece. As a young

boy he lived through the Second World War and Greek Civil War and came

to Australia in 1950 at the age of 14. In November 2010 he was interviewed

by Pollitecon Publications editor, Victor Bivell.

printable

version

printable

version

VB: Tanas, tell us about your early memories.

TM:

My early memories... I was a child, I used to play with the kids. Everybody

was very very poor. I can remember neighbours who hadn't eaten for three

days. We baked some bread, and the lady came over, and she asked my

baba, my grandmother, to give them their bread because she had four

kids, three girls and a boy, and they hadn't eaten for three days, they

were very poor. And my grandmother gave one loaf of bread. And she was

sure thankful for receiving this bread.

TM:

My early memories... I was a child, I used to play with the kids. Everybody

was very very poor. I can remember neighbours who hadn't eaten for three

days. We baked some bread, and the lady came over, and she asked my

baba, my grandmother, to give them their bread because she had four

kids, three girls and a boy, and they hadn't eaten for three days, they

were very poor. And my grandmother gave one loaf of bread. And she was

sure thankful for receiving this bread.

But we weren't too bad. We had some sheep, two bulls, one cow and a

mule. We had properties we looked after. We lived in a house, my grandfather,

my grandmother, my mother, my two sisters, my brother and myself, my

uncle and my aunty and they had two kids. We all lived in one house,

and then we separated. We divided the sheep into three. One share to

my grandfather, one to my uncle and one to us. My brother looked after

the sheep, and I looked after the cow and bulls.

VB: It sounds like life was very tough for everyone.

TM: Yes, it was very tough. Before this happened my brother went to

work for someone else, like a servant, for one year to earn a living.

While I picked up a lot of neighbours cows and bulls. I used to look

after them for about three years. At the time I was only about eight

years of age. Eight to eleven I did this. And after we separated things

with my uncle there, of course I took over looking after our own cow

and two bulls and did the home duties there. I tried to collect food

for the animals for winter. And doing other things. We had some fields

with grass for hay; we cut the grass and put that away for the winter.

We had trees. We called them "shooma" and "dapie".

We used to chop the branches in summer and I used to pick them up for

the sheep in winter. The sheep gave us wool, and we made our own clothes;

and milk and we made our own cheese; and they gave us meat too.

Yes, life was very very tough and very poor. We had all sorts of problems.

A lot of people didn't have much to eat. We weren't too bad for eating,

but we didn't have a lot clothes to wear. Particularly shoes. The first

pair of shoes I remember, I must have been about eight. Before I was

eight I never wore shoes at all. I didn't have a pair of shoes. During

the German occupation in the Second World War, my father sent five pounds,

five pounds was good money in those days. My grandfather with my mother,

they went to Lerin, and they bought a few things and they bought me

a pair of shoes. Before that I had bare feet and they used to split

underneath my toes. They always used to bleed when I was walking in

the heat. It was pretty hard to walk.

VB: Did you go to school?

TM: Yes, I did, to a Greek school. I went for about a year and half,

two years. It was very very tough for us because we had to learn Greek.

We weren't allowed to speak Macedonian. One day I spoke in Macedonian.

The teacher heard me and took me into the room, and asked me why I spoke

this language, what language was this? I didn't know the difference.

It was Macedonian. They told me it was "voolgari"; it means

Bulgarian. I didn't know what was Bulgarian, but I got the cane on each

hand twice for speaking the language, which was my own language, Macedonian.

I didn't know the difference. All I knew we went to school to learn

Greek. We knew nothing else about all this. I was only about seven or

eight years of age.

VB: What sort of things did you learn or did they teach you at school?

TM: They taught all about Greece. They tried to make us Greek. Everything

was for us to learn the Greek language. Nothing else. As far as we understood

there was nothing outside Greece. It was all Greece all over the world.

VB: What language did you speak at home?

We spoke only Macedonian. We weren't allowed to, but it was the only

language we knew, Macedonian. We used to put some covers on the windows,

to make sure no one could hear from outside, especially in the evening.

We'd cover our window with blankets. Very thick blankets, made out of

sheep. So people who went past wouldn't hear what we were talking about.

Outside we still spoke Macedonian. If we saw a policeman or something

we either shut or spoke Greek if we knew. But a lot of us didn't know

how to speak Greek.

VB: What do you remember about your father, Vane?

TM: I don't remember too much about my father, because my father left

when I was about 18 months old, and I never saw my father until I was

14 years of age in Australia. My father left in 1937 to come to Australia,

and I never saw him until 1950. My mother, she looked after us, she

had to work very hard to provide food for four of us, plus we were trying

to provide for ourselves but we were very little. Life was very tough.

VB: Your father spent your childhood in Australia. What do you remember?

Did he send money, and how did you stay in contact?

TM: We used to write letters to him. But there was a lot of time in

between. Probably one letter a year. It was not very easy to write letters

from Macedonia to Australia or back. My father sometimes used to send

money. Five English pounds. Five pounds was maybe once a year or every

couple of years. That was big money for us. A big help. My father wasn't

earning much money over there in those days. He used to work in the

bush and what he told me they used to work for ten shillings a week

or just for the food sometimes. And he'd take 12 months or more to save

five pounds. And he used to send it to us. But mostly we had to earn

our living ourselves, along with help from him. It helped us to survive.

That's why we survived.

VB: What do you remember about your mother, Ristana?

TM: My mother provided all the food for us. She looked after us; and

after me for 14 years. She had to work in the paddocks. We had to plough

the paddocks, where there were bulls, two bulls together. And we worked

to plough all the paddocks and put seeds there. And the seeds grew to

wheat or "chanitsa", or "rush" which I think was

rye. Rush is similar to chanitsa but the bread was a bit darker and

harder. That meant we could eat less of that one. With wheat you can

eat more. We tried to eat less because we didn't have enough. My mother

was always working the paddocks, and at home cooking things for us to

live.

VB: Did you grow your own foods? What foods did you grow?

TM: Yes, we grew wheat and rush and "chenka" or corn. We

had two bulls to plough the fields. We had a garden, there were a lot

of gardens. We grew our own potatoes, tomatoes, paprika, onions, leek

and other vegetables; we used to grow all these for ourselves. We used

to grow rush, which is like wheat but poorer quality. We made our own

bread. We used to do everything ourselves. There was very little we

used to buy from the city because we didn't have any money. Money was

not used much at all. It was always with food. Even with the work we

used to do for people, they would pay with rush, with wheat. Things

like that.

VB: Tell us about your eldest sister, Fania.

TM: Fania, she was the oldest of the family. She had to do a lot of

hard work. She had to do a lot of home duties, she had to work in the

paddock, she was very responsible for our family, for all the family.

She was the oldest one and she was working like my mother. My mother

was working and she was with her. She was the oldest child in the family.

Then in the Civil War she was taken by the partizans. She was there

for about six months, and at the end of the Civil War she was let out

and she came home.

When she came home she was in the newspaper, because they were very

young, three children taken by the partizans. And when they came home

they put it in the paper, in the news.

VB: How did the partizans treat your sister?

TM: She didn't have any problems. They looked after her because they

were young kids. My sister was 16 years of age, and the other girl was

the same age, and Tanas was only about 14 of age. They were only young

kids. That's why when they came home they were put in the paper because

they were so young and they were saved. They weren't killed or anything

like that. It was in the radio news and in the paper news.

VB: Who were the other two children?

TM: They were friends of ours. Para Slifkina and Tanas Slifkin, brother

and sister. They were together with my sister.

VB: Tell us about your brother, Mitre.

TM: Mitre, again, he was a bit older than me, about two and a half

years older. He looked after the sheep. He became a shepherd, and he

was a very keen shepherd. He was looking after the sheep. He went to

wash himself at a spring and unfortunately for him he stepped on a mine.

He lost his leg there. No one was near him to give him help. The blood

ran out, and they took him to Lerin, Florina, and by the time he saw

the doctor he was virtually dead. And he died at 15 years of age. He

died in 1948.

VB: In what year was he born?

TM: He was born in 1933. I'm not sure which month. In the early summer,

spring to summer.

VB: Tell us about your sister, Kata.

TM: My sister, she was the youngest of the family. When I left and

came here [Australia] I was 13 nearly 14, and she was about 12 years

old. She did her part too. Working hard. When I left she was looking

after the bulls. When my brother got killed, I became the shepherd,

looking after the sheep. And my sister looked after the bulls and cow.

And she did a lot of home work, and work in the paddocks. When I left

in 1950 she was only about 12 years old, from then on I didn't see her

until she was 16 years old.

VB: What do you remember about your grandfather Stojche and your grandmother

Lozana?

TM: My grandfather Stojche was very honest. He didn't want us to get

in trouble. He didn't want to give anything away, at the same time no

one wanted to step on his food. He was a little bit of a hard man. But

very honest. He made sure we kids would grow up the right way, without

getting into trouble by pinching other people's properties or stuff.

My grandmother, she was a very kind woman. She never ever told us off.

She was always telling what was best for life. She worked very hard

looking after the house, with six children in the house.

The same applies to my grandfather. He was very hard working man. While

he didn't want us to get in trouble, he didn't want anyone taking his

property, too. Because he worked very hard all his life, together with

my grandmother. They were very hard working people. Very honest people,

both of them.

My grandmother was such a nice woman. She never told us off. Once she

told my brother off, and my brother never stopped crying. He burst out

he was so surprised that baba [grandmother] would tell him off. She

was such a kind lady. I can never forget her.

The reason my grandmother told my brother off was this. We set a bonfire

three times a year and we used to collect wood from neighbours and from

the bush to burn all night. And this particular bon fire there was some

wood left, and my brother and two others, Vasil Mechkarov our cousin,

and Tanas Slifkin a friend of ours, they were a little bit older and

they sold the wood to a shop and they bought some wine. And then they

went to Vasil Mechkarov's house and they drank it, and they ended up

a little bit drunk. Tanas Slifkin's father came and took him home, and

Vasil Mechkarov stayed at his house. And I went and took my brother

home. When he came home my grandmother said "Shame on you, I haven't

seen your father drunk and now I'm seeing you to be drunk." And

he was so upset when my grandmother told him off like that, he started

crying, he didn't stop crying for hours. We tried to calm him down,

but he was so surprised that baba would tell him off.

VB: What other relatives and friends do you remember?

TM: I remember friends and boys, we used to play different games. We

would play marbles. We used to make our own marbles from clay. And balls.

We didn't have any balls to play with, but before I came to Australia

my father sent me a bit of money and I bought a soccer ball. Not a proper

soccer ball, like a plastic soccer ball. And on many days all the boys

would gather at my house and call me to play soccer. Because we had

never seen a soccer ball in our lives. The first time I saw one was

because my father sent me a bit of money. We used to go and play soccer,

which was good.

That was during the summer. In the winter months there was snow and

we used to ski in the snow. All the boys used to fight with snow balls.

We used to make a snow man, and fight for possession of the area with

snow balls.

VB: Lerin was your nearest big town. Did you go there often?

TM: I went to Nevoleni, which is just out of Lerin, twice, but I never

went to Lerin. The first time I went to Lerin was just before I came

to Australia. My father sent money for me to go and buy myself some

clothes, and different things to come to Australia. That was when I

was 13 years of age. Before that I never went to Lerin. I heard about

it. I knew about it. But I never went to Lerin because there was no

money, we didn't have any money to spend there, so what's the use of

going to Lerin when you don't have any money? Plus it was a long walk.

VB: Was Neret a purely Macedonian village?

TM: Yes, in Neret they were all Macedonian. The Greeks had a police

station there, they were the Greeks. And there were Greek teachers,

Otherwise there was no Greeks in the village, but there were ‘Grkomani'.

VB: What are your happiest memories about the village?

TM: My happiest are when I was playing with the boys there. Just playing

different games with the boys. Survival. Being with my brother, we grew

up together, my brother and my two sisters. And plus a lot of neighbour's

boys, we used to play together, like any other young kids. An open life.

We had a very poor but very happy life. We enjoyed our life, even though

we were very poor. There were no activities. We used to make our own

games, we couldn't buy things, we didn't have any money, but we still

survived. I still have happy memories because to me as a kid I would

give anything to go back to that.

VB: What do you remember about the Second World War?

TM: I remember the Second World War, the Germans came to our village

and they were taking all the mules and horses for labour for them to

take stuff up the hills. And as I was eight or nine years of age I was

working very hard at the time for one so young. Our paddocks were very

far from the village, up the hills, and often we slept there. I had

to come down from the hills with mules loaded with chanitsa, rush, and

bring it to the village and take it home and leave the village before

the Germans blocked the roads.

That was before dawn, very early hours, and as I was eight year old

I was very frightened to do this. But unfortunately we had to do it

as part of our life. We used to work from six, seven years old. Doing

what people do now when they are 20 years old. People expected us to

do it, even from eight or nine years old.

VB: Do you remember much about the Second World War and how it affected

your life in the village?

TM: I do remember a little bit, because most of the time we were out

in the paddocks, looking after the animals and working with our parents,

my brother and sisters.

But I can remember the Germans coming in our village, in the middle

of the village, "stred selo" we call it, or ‘ralishche'.

They were big men.

And I can remember the Bulgarian army coming to the village too. I

remember one Bulgarian army man who said "I'm a teacher. After

the war I'm going to come and teach you a lot of things". He was

a very kind man.

Then I can remember that the Germans were pushed back. The Germans

were retreating back past our village, and the village was bombarded.

VB: What was life like during the Civil War?

TM: Terrible. Terrible. First of all, my uncle went partizan, and because

he did the Greek army came and burned our house. They burned everything

in the house except what was on our shoulders, our bodies. We didn't

have anything left. No food. No clothes. Nothing. They burned everything.

Complete.

And then from there we moved on to my uncle's, which was my mother's

main house where she came from. And the partizans bombarded the village

and hit the house. We had to move from there to another house. To Petre

Mechkarov's house, which was next door to our original house. We moved

there. Then the Greek army bombarded the village and hit that house.

We fixed the damaged roof on my mother's original house and we moved

back there. We had to shift three times.

Many many times when we used to go to look after the bulls and cows

and sheep, the Greeks would shoot bullets, or fire bombs. ‘Allme'

they used to call it, which they would shoot up and they would come

straight down. Every time we went out of the village they used to fire

‘allme' and try and kill us. After that we couldn't go out from

the village up. We had to go down from the village. When we went down,

same thing. Every time they saw people going out of the village, they

would bombard them, and try and kill them. A lot of people got killed

or injured.

My brother got killed in 1948 with the mine.

The partizans also took my mother to work for them, and they took my

oldest sister, Fania, too.

VB: What sort of things did you have to do to survive during the Civil

War?

TM: We had to work very hard. We couldn't go to the city, Florina,

we called it Lerin. We couldn't buy many things from there, particularly

salt. We couldn't buy salt because they reckoned if you don't have salt

you can't eat anything. They used to have someone outside the city to

search everyone who came out to see what they had bought. We weren't

allowed to buy too many things at all. We ate bread and everything without

salt. We still worked very hard to survive, but on very poor quality

food. That was part of a strategy to stop the partizans getting salt.

First of all the Macedonians partizans entered the war to separate

the Macedonians from the Greeks, but unfortunately later on they got

mixed up with the Greek Communist Party and became communists. Even

if we did win the Civil War we would have got nothing by the end because

we would have still been dominated by Greek communists.

VB: Tell us about the Greek Civil War and how it affected the village

and your life?

TM: During the war started we had to shift from our village to another

village, to Nevoleni, that's near Lerin. We stayed there for a while.

But we couldn't live there. We didn't have properties. We didn't have

anything. We had our sheep. We didn't have enough food at all. So we

had to go back to our village. And during the time we were there, the

Greek army kept coming. They were very severe. Punishing people. Burning

houses. They burned houses. If some people had gone partizan, they would

burn their houses. On the other hand the partizans would come and burn

the houses of the people who had gone to the Greek army. For us it was

like living in hell.

Once the partizans bombarded the village, and that is when they hit

my mother's house. The Greek army bombarded the village many times.

We were sitting between three big hills. One side of the hills were

the Greek army, and on the other side of the hills were partizans. Each

time they would fight, the Greek army would bombard the village because

there were partizans in our village.

One day I was looking after the sheep after my brother was killed.

Some partizans went up to the hills where the Greek army was, and the

army chased the partizans down. We saw them coming down. But we were

told by my grandparents to say "We saw nothing, we know nothing".

And they asked us questions and we told them we knew nothing. We knew

everything that was happening in the village, but we told them nothing.

They took us there, and our sheep went over one of the hills, and there

was one very bad soldier there, he took us, me and my cousin, Giorgi

Mechkarov, and he stood up and kept saying "Tell us what you saw".

We said we saw nothing. So he took my cousin away from there to one

side, me on the other side. And he came to me and said "Your friend

told us you saw the partizan coming down. We are going to let him go.

But if you don't tell us we are going to shoot you. I said "If

he saw them, I don't know, I didn't see them". But I did see them.

But I wouldn't tell him, because I was told by my grandparents not to

say anything. That's what we were told.

My cousin told them the same thing.

Then he took me up, brought my cousin, made us stand up. He put my

cousin in front of me: he was a little bit shorter, I was a bit taller,

and I was behind him. And he aimed with a gun. And he fired the gun.

We just dropped dead. We thought he'd killed us. But he didn't kill

us. He just tried to frighten us. We were scared. Very very scared.

And then another soldier, a captain or sergeant who was at the top,

said "What the hell's going on there?" And this particular

solder said "We caught these partizans here."

We were 12 years old. He called us partizans, hiding in the bush. And

we told him we were shepherds. We told him one of the soldiers saw our

sheep go over the hill, but this particular soldier wouldn't believe

us. When the sergeant took us up there, we were crying. We were very

scared. Crying. And he said "Sit down." And he made me sit

on his right hand side, my cousin on the left hand side. He tried to

pat my knees. "Don't cry," he said. "Don't worry. Nothing

is going to happen to you." We tried to tell him that he was going

to kill us. He said "No. No. He only tried to scare you. When he

said that we felt a little bit better. "Don't cry," he said.

"I've got kids like you." He was a very kind gentleman. He

was a good man. He was a Greek, but he was one of the few good ones.

Then they took us to one of the other hills. The army had come down.

And they asked us a lot of questions about our parents, where my father

was. I told them my father was in Australia. And the same with my cousin

- he told them his father was in Australia too. They asked about the

village. We told them that as you can see we get up early to look after

the sheep, and we go home late. We don't go to the village. We don't

know what's there. We did know, but we said we didn't know. So they

rang up Florina, Lerin, to find out if we were telling the truth. If

our fathers were in Australia. They checked out and they found that

both our fathers were in Australia and then late in the afternoon they

let us go.

And they said before you go home you must go and collect your sheep.

I said "All the hills we can see, all the soldiers there. Greek

army. They are going to kill us." He said "Don't worry about

this particular person. Don't worry about them. They are not. But keep

an eye for the partizans. In a way he was very right, because as soon

as we tried to pick up the sheep the partizans started to bombard the

area which we just left. Luckily we escaped. I don't know if any soldiers

got killed or not.

Then we went and picked up the sheep, and came down to the village.

When we got to the village we had another partizan waiting for us because

he could see exactly what was happening and there were a lot of partizans

in our village. He stood there and kept asking questions. What did they

say? What did they do? He kept asking questions but we told him nothing,

because we didn't know anything about it. Then we went home. We were

very frightened. We were so scared to go out the next day. Life was

full of fear. We lived in fear. We lived day by day.

VB: And sometimes did you fear for your life?

TM: We feared for our lives every time we got out of the village. We

did fear for our lives. One day we were looking after the sheep and

there was a bit of trouble with the partizans. They killed two Greek

soldiers at the bridge between Lagen and Neret. The Greek army started

firing at every person they saw. They started firing at us too. We laid

down, hiding, I happen to lay in a little creek, and then my cousin

stood up. We were told that if you get hit you always feel very very

hot. I was so scared I felt very hot in my back. And I kept lying there.

My cousin said "What are you doing, Tanas?" I said "I've

been hit in the back." He said "There's no blood there."

When he said no blood I felt a bit better. After they stopped firing

I got up and I jumped out and tried to run towards my sheep.

Things like that used to happen all the time. Another time we went

to the sheep, another area there. For no reason at all the Greeks started

to fire ‘allme'. Like rockets. They go up and they come straight

down. We could hear when they fired the bombs - boom boom boom. I heard

them three times. Boom, boom, boom. I chased the sheep down away from

there, that area, then I lay down, there was a little footpath. The

area was downhill. I happen to lie downhill when the bombs fell. One

fell a fair distance from me. But another just above me on the hill.

This particular ‘allme', we call it, they used to spread upwards.

They didn't spread downwards. I wasn't hit but I was covered with sand.

There was sand over me. When I went further down my friend shook all

the sand from my back and head and everywhere. We feared for our lives

every time we got out of the house.

On many occasions it happened. When we went there for no reason at

all the Greek army would start firing. If they saw people in the area

they would fire. I'm lucky to be alive. A dozen times I could have been

killed. Many times they would start firing and they killed a lot of

sheep. And some of the bulls. And some people got killed. I still call

myself very very lucky I'm alive. Unfortunately my brother was not so

lucky at all.

VB: Your sister Fania was taken by the partizans. What happened?

TM: They took her. They used to take anyone who was over 15 or 16 years

of age. She was 16. They took her to serve the partizans. She was a

bit too young and they didn't send her to war. She served there, working

for the partizans. Lucky for us or for her shortly after about six months

there the war finished and she was allowed to come home, like everyone

else.

VB: What did Fania do when she was caught?

TM: The partizans were picking the young girls and boys from the village,

during the evening and night. And she was lucky enough to escape from

their hands, and she hid. When we went to take her food, we found she

wasn't there. But then they were going to hold me. I was only 12 years

of age and they were going to take me as a partizan. My mother kept

crying. In the meantime, somehow the Greeks found out what had happened

in the village. There were always people who would pass on information.

They started to fire bombs in the village. And everybody tried to hide

for their lives. They let us go. And then my sister was home, hiding.

A couple of days later she tried to escape from the village with a couple,

Tanas Slifkin and Para Slifkina. The three of them. Somehow, somebody

informed the partizans which way they were going to escape and they

were caught.

They were going to escape to Lerin, Florina, and they got caught and

they were taken by the partizans for the best part of five or six months.

And lucky enough the Civil War finished and she came home. We lived

a bit normally. Not long afterwards I left in 1950.

VB: The partizans took your mother, Ristana. What can you tell us about

that?

TM: They took my mother because my mother went to Lerin to do some

shopping. A chap by the name of Kirko Marin said where's your kids?

Because people had sent their kids as refugees, as begaltsi as we call

them. But we didn't go to be refugees, and when he said "Where's

your children?" My mother said "At home." He said "Didn't

you send them with the other children?" And my mother said "No,

I didn't." And unfortunately Kirko Marin had some relatives in

the village and one relative, a lady, had one daughter, and that particular

lady when she went to Lerin Kirko Marin asked her where's her daughter

and she said her daughter was part of the refugees. Kirko Marin told

her off her because she had one daughter and she had sent her away,

while Ristana Mechkarova had four children and she didn't send any.

The lady came back to the village and complained to the partizans about

my mother. She dobbed my mother in, and told the partizans what happened

plus more lies. The partizans took my mother as a prisoner there, as

a working prisoner. She worked there for a long time, for eight or nine

months. In the meantime my brother got killed while she wasn't home.

And of course when she came home they took my sister away. So we were

always depleted as a family. We were never together as a family during

the Civil War. There was always someone missing.

VB: Who was Kirko Marin?

TM: Kirko Marin came from "poljeto" as the Macedonians call

the plains area, from another village from a long way. He got married

in Neret. He was poor, so our people decided to make him like a ranger,

we call it "poliak", like a ranger in the village so he could

survive to live. In the meantime, Petre Markov, he was a partizan, a

very strong partizan, and the whole police station was very scared of

him. Every time he came to the village during the night they fired at

him but they couldn't kill him. And this Petre Markov said the only

way they are going to kill me is when I sleep, because he was a very

heavy sleeper. And this Kirko Marin, he was a ranger, met this Petre

Markov and Petre Markov asked him to go and bring some food. And Kirko

Marin came to the village, to Neret, to get some food. Instead of bringing

food he took the police station, all the police there. Petre Markov

was asleep. Unfortunately Petre Markov as I said before was a very heavy

sleeper. They started to fire at him. It took them quite a while to

kill him apparently, because he turned to one side. They reckoned if

he turned once more he would have fallen into a dip and they wouldn't

have been able to kill him. But they killed him.

By doing that Kirko Marin became a pretty important person to the Greek

police station or to the army. And they made him a big boy. He controlled

the village. Whatever he said for our village, that's what happened.

If he said burn all the village the Greek army would have burned all

the village. And Kirko Marin came to the village with the army to burn

houses and Kirko Marin recommended which house to be burned, who were

the partizans. And because my uncle was a partizan and they decided

to burn our home.

And every time people went to Lerin Kirko Marin was standing outside

Lerin, Florina, he and the army would search every person who came out

of the city, to see what they had bought, and make sure they didn't

buy too much food, didn't buy salt, like I mentioned before, and things

like that we weren't allowed to buy. He did what he wanted. Then afterwards,

he was always in control of the village. Because he was a spy, a spion,

a spy.

I was told that after the Civil War finished people didn't want him

and he had to leave the village.

VB: Was your brother a child refugee?

TM: No, because he was sent to school in Bitola before the Civil War

with other children, but he didn't want to stay there on his own. He

felt very lonely. So he came home immediately. And from then on he didn't

want to go anywhere. So that's the reason he didn't go as a child refugee.

And because he didn't go, none of us went there. If he had gone, we

all would have gone. But because of him we all stayed home.

VB: What happened to your brother?

TM: My brother took over as shepherd after we divided things with my

uncle. He was very clean and always wanted to have a wash and change

clothes whenever possible. That particular day he wanted to come home

to wash and change his clothes. But the man who was in charge of the

shepherds said "You can't go home until we pass all the wheat farms

and fields over there". By the time they went through it was lunch

time, and he could go. But being lunch time he wanted to milk the sheep.

He went to wash himself, his feet, at the spring water that was there.

But at the spring water there were a few flat stones for walking and

unfortunately two mines under the stones. When he stepped on one of

the stones it blew up and cut his leg. The other shepherds ran away

as they thought the Greek army were firing bombs at them. Some of the

other boys heard my brother, Mitre, crying for help. And the man in

charge of the young shepherds told the other boys to be quiet and sit

down so no one would be hurt. And by the time the Greek soldiers came

from the hill and attended to my brother, most of the blood had run

out. They strapped him up and the young shepherds came out and joined

the soldiers. All Mitre said was "Is my mother back yet?"

My mother was still prisoner with the partizans. He was told no, and

they were the last words he spoke. And from there they took him to Lerin.

Florina. The doctor saw him but he was virtually dead on arrival.

The army herded the sheep to the area and a second mine was blown up.

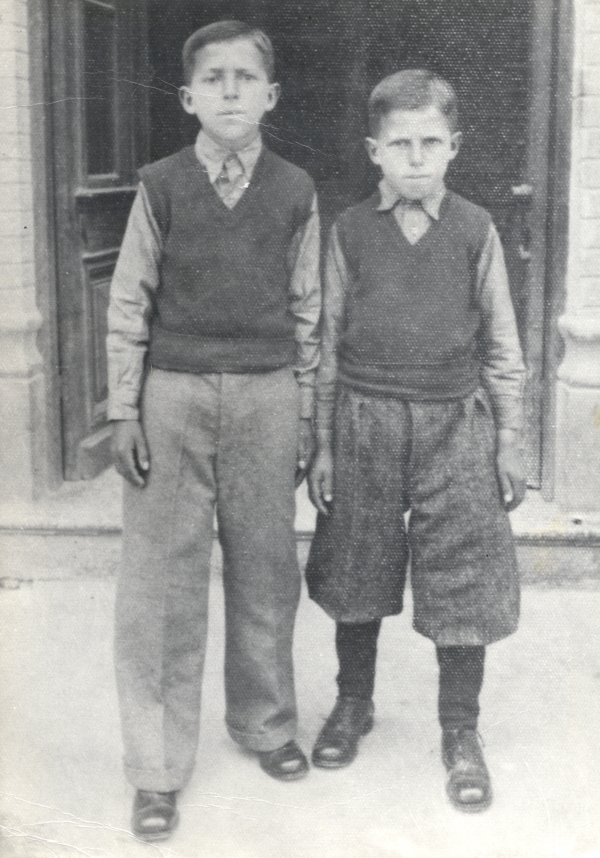

Above: Young brothers: Mitre and Tanas Mechkarov.

Below: The Mechkarov family after Mitre's death. Back row: Tanas Mechkarov

and his sisters Fania and Kata. Front row: The children's mother Ristana,

grandfather Stojche and grandmother Lozana. Their father, Vane, was

working in Australia.

VB: Your father was in Australia and your mother was with the partizans,

so what did your family do?

TM: We had to survive the best we could. Before my brother was killed,

I looked after the bulls. I was also looking after the neighbours' bulls.

I'd take them to the fields and up the hills so they could feed. Every

day right through the summer. And we got paid for it. Money or wheat,

food, to survive. When my brother got killed I took over the sheep,

I became the shepherd, and my sister Kata took over the bulls and cow.

My young sister looked after the bulls. At 10 years of age she had responsibility

to earn a living. My older sister Fania had to more or less look after

us with my grandmother and my grandfather. My grandfather couldn't do

too much at that stage as he was a little sick. So most of it fell to

my sister and my grandmother. We had to keep working and survive the

best we could.

VB: After your mother returned home, did you have to move village for

a second time?

TM: Yes, we did. All the village, they were shifted to Nevoleni. And

we stayed there until after the Civil War finished, and then we came

home. And after the war my sister came home.

VB: What happened after the Civil War?

TM: Because my brother got killed, and what happened to my mother,

my grandfather wrote a letter to my father to take me to Australia before

they killed me too. And things started moving. My father got a permit

for me. So we went back to the village, and resumed our normal work.

When my permit arrived to come to Australia I came to Australia. I was

13 years of age when I left, and I had my 14th birthday on the boat.

VB: What year did you leave the village and what was the trip on the

boat like?

TM: I left on the 3rd of March 1950 and arrived in Australia on 17

April 1950. The trip itself was horrible. Because the boat was the Sabastiono

Caboto, an Italian boat they used in the [Second World] war to transfer

food from one place to another.

And the food we were getting was terrible, three times a day - spaghetti.

In the morning we'd have spaghetti, for lunch time we'd have macaroni,

evening we'd have pasta. Virtually they were all macaroni. Towards the

end we were so sick of the food we couldn't even eat it. After the meals

they used to give us a piece of fruit - an apple or orange or banana.

Towards the end we'd just go and pick up the apple or whatever they

gave us and just walk out without eating at all. We just couldn't eat

it. When I came to Australia I was so sick of spaghetti I didn't even

want to look at it. It took me years before I could eat spaghetti. I

like it now.

VB: Tell us about your first meeting with your father when you arrived

in Australia and what happened?

TM: I never knew my father. I wrote him a letter before I got here

saying to come and meet me at the port because I didn't know who he

was. Whoever came there would pick me up. I didn't if it was going to

be my father or anyone else. My father came and picked me up from Fremantle.

From there he took me to Lake Grace. I stayed there for about three

years. In 1953 I decided to come to Perth.

VB: How did you recognize each other?

TM: I didn't recognize him. My father just came around and said "Are

you Tanas?" I said "Yes", and he said "I'm your

father". And we met there. He hugged me and he kissed me, and all

of this, like any father would do. I was very proud and happy to meet

my father. I knew I had a father but I had never met him, never seen

him. It was very exciting. I looked up to him. He was my father. Every

time the boys back home would say "My father this" or "My

father that" but I couldn't say anything. My father was too far

to help us. We were very disadvantaged. Regarding an argument with the

kids back home, or doing things, everybody would say "My father

this" but we couldn't say that. We had no father. We knew we had

a father, but a long way from home, and he couldn't help us.

VB: What was life like at Lake Grace? What did your father do for a

living?

TM: My father had a restaurant there, together with my uncle. I went

to school and worked at the restaurant. For me it was a very hard life

because I couldn't speak English. There were no kids to play with. The

boys didn't like me. They used to pick on me, because I was the only

foreigner. My father got sick in 1952, and he had to have one of his

kidneys taken out. During that time I stayed with my uncle in Lake Grace

while my father was in Perth. After school the boys would pick on me,

and they used to fight with me all the time, and I had to leave school.

I started working full time at the restaurant, and my uncle sold the

business in mid 1952. I stayed with the new owners; they were very good

to me. I stayed with them for about nine months. In May 1953 my father

bought a shop in West Perth. I came to Perth to work in the shop, and

from then on we lived in Perth.

VB: What sort of shop did your father have, and did you help him?

TM: Before, there were no supermarkets. It was like a corner deli,

grocery, fruit shop, everything. Like what a supermarket is these days

but in a smaller version. That's the sort of shops they were then. We

worked in the shop, both of us, until 1954 when my mother arrived. My

mother was a very hard working woman back home, and she couldn't stay

there in the shop. After nearly 17 years of separation with my father

to 1954, they decided in 1955 to go to Manjimup to grow tobacco. My

father and my mother went to Manjimup to grow tobacco and I ran the

shop until 1959 when I decided to sell and get out.

VB: When your mother came out in 1954, who did she come with?

TM: My mother came with my youngest sister, Kata. They left my other

sister Fania back home because she got married and had a little child,

Mitre. They stayed there until 1955 and that year with her husband and

baby the three came together to Australia.

VB: Where did your family get the name Mechkarov?

TM: Our family line goes Micho, then Giorgia, then Mitre, then Stojche,

then Vane, then myself, Tanas. We used to be called Micho, as my great

great great grandfather was called Micho, and we were called Michovi,

after his name. His son was Georgia, like George, Georgia, and we were

then called Georgioi. He was a pretty strong man. He went to collect

some wood with his donkey. He tied the donkey to a tree, and he went

and chopped some wood. When he was ready to leave he went to get his

donkey and a bear had killed the donkey. My great great grandfather

Giorgia, called out to the bear and the bear turned on him. He ran away

and the bear chased him. He ran to a tree and climbed to a part of the

tree where it was chopped at the top. A short tree. He climbed the tree

and the bear grabbed the tree. As the bear grabbed the tree, he hit

the bear with the axe he had in his hand and split the bear's head.

When the blood started to come down over his eyes the bear couldn't

see and my great great grandfather came down and killed the bear. He

took the bear's skin and sold it and bought a horse, which was much

better than a donkey. A donkey is a simple form of transport, then a

mule is a little better, and a horse is at the top. And people started

to call him "Giorgia who killed the bear." "Giorgia the

bear killer." The word for bear is Mechka. "Giorgia who killed

the Mechka." So they called him "Giorgia Mechkarov koj otepa

Mechka" [George Mechkaro who killed a bear]. So Mechka, Mechkaro,

Mechkarov, Mechkarovi. That started the name Mechkarov.

When there was no reading and writing people used to change their surname

to that of the first name of the oldest man of the house, but when schools

came along they started to keep the same surname.

VB: Did your grandfather and grandmother tell you any stories about

the Turks?

TM: They told me stories like dedo Giorgia who was always fighting

against the Turks, trying to get rid of them. There were quite a few

people in the village like him. The Turks always used to beat them up.

Every time trouble started, they would pick up the people they knew

were against the Turks, and they would beat them up. One day my grandfather

Giorgia, he had a pig, and the pig escaped somehow from the yard and

went out. A ranger, we call him "poliak", shot the pig and

took him to the centre of the village. And he called my grandfather

Georgia to have a look. My grandfather said "Why did you shoot

it?" He said "Well you shouldn't have allowed him out of the

yard." He said "He got out. You shouldn't have shot him. You

should have told me about it." He said "You let him out and

I shot him." That's how the Turks were working. My grandfather

Giorgia said "I'll put his tail in your mouth one day." And

very shortly after that, we used to make a big pile of branches from

the dapie trees for winter to feed the animals. And somehow the big

pile of branches caught fire and they found the ranger's body in there.

Then the Turks took my dedo Giorgia and there were others because there

were a lot against the Turks, and they beat them all up. They beat him

to the stage where my grandfather Giorgia died as a result of the beating

he had from the Turks. That's the life we had from the Turks. Similar

to the life with the Greeks.

VB: What sort of things did the Greeks do to keep control of the village?

TM: They used to have a lot of spies. People that they would pay to

inform the police if there was any activity going on in the village.

Like if you were speaking Macedonian. Or if we were talking against

the Greek government. Or whatever. They had paid people. They used to

pay the people just to inform them. Sometimes people didn't like someone

in the village, and they would tell the police stories that weren't

true. People used to be picked up and be bashed and sent to prison for

nothing. Bash them up for no reason at all because this particular person

who was paid by the Greek government said this person did something

that they never did. The Greeks would take their word about them being

bad people. But people weren't bad at all. These spies, these informers,

told the police station and the police didn't ask questions, if it was

true or wrong. They just took the spies' word for it. And a lot of people

used to suffer for no reason at all, for nothing. It used to happen

all the time.

Postscript:

When he arrived in Australia, Tanas lived in Lake Grace with his father

and uncle Jim Vlahov and cousin George Vlahov. He went to school for

six months and then worked at the restaurant owned by his father and

later new owners. In 1953 he came to Perth with his father who bought

a delicatessen/ grocery shop with a house attached in Colin Street,

West Perth. Tanas worked there for six years and then worked for the

retailers Associated Grocers (now IGA) and Boans (now Myer).

On 20 January 1963, he married Zivanka Sideris and they had three children:

Anne, Mary and John.

Looking for better opportunities, he worked for the Education Department.

But his interests were in business and property. In May 1965, he purchased

his own business - the International Club in James Street, Perth. After

8 ½ years, he sold the International Club and bought his first

Shell Service Station. He spent 23 years in the service station industry

and in this time built and developed several service stations.

For many years Tanas lived in North Perth with his mother and father.

He then built a family home in the suburb of Balga (now Westminster)

where he and his family lived for 17 years. In 1985 Tanas and Zivanka

built a new family home in Stirling.

In his spare time, with his wife he bought and renovated houses for

rent and sale. He was also a long term investor in land and formed and

led successful syndicates with his extended family and friends.

In his early years he also renovated a small shopping centre in the

suburb of Mosman Park and later built the Merriwa Shopping Centre with

Paul and Rene Ristovski. Tanas and Zivanka along with Paul and Rene

ran the Merriwa Supermarket. Tanas and Zivanka bought Paul and Rene

out of the business in 2000 which they continued to run until 2002.

For many years Tanas worked voluntarily for the Macedonian Community

of Western Australia and the Macedonian Orthodox Church. He held the

positions of Assistant Treasurer for two years and Treasurer for five

years. For many years he was also on the Neret Village Social Club committee

as Treasurer.

Tanas was fluent in three languages. He was aware that circumstances

had prevented him from enjoying a full formal education and he always

encouraged learning in others. He had an enquiring mind and was interested

in national and international politics and current affairs, Macedonian

affairs, and social justice.

Tanas passed away on 6 December 2016, aged 80. He left behind his wife,

Zivanka, daughter Anne, son-in-law George, daughter Mary, son-in-law

Vic, son John, daughter-in-law Aneta, grandchildren Cassandra, Jacob,

Michael, Sydnee, Gemma, Justine, Alexander, Kristofer, and great grandchildren

Emilia and Vincenzo.

© Copyright Tanas Mechkarov and Pollitecon Publications, November

2010

Source: www.pollitecon.com